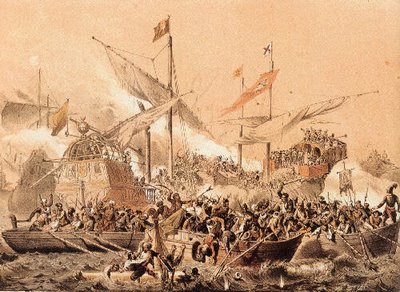

The third battle of Lepanto

The third battle of Lepanto is probably the second most famous galley engagement in history (the first being the doomed Spanish Aramada). On the 7th October 1571, the Muslim Ottoman Turks met the Christian Holy League in a naval battle in the Bay of Lepanto, in Greece, known today as the Gulf of Corinth.

The Ottoman Turks were the greatest of all the Muslim powers and at the time of Lepanto they were at the peak of that power. Attacking Europe was how the Ottoman Turks spent their free time and this was just another of their attempts to 'convert the Europeans'. Their empire already had dominion over most of the Mediterranean and they had already won the first and second battles at Lepanto and no doubt were in good spirits as they lined up their ships. Their commander Ali Pasha had some 230 galleys and circa 55 galliots (which are lighter than ordinary galleys) under his command. He also had two allies fighting alongside him; Chulouk Bey of Alexandria and Uluj Ali (who was an Italian who converted to Islam after his capture by the Ottoman Turkish ‘Barbary pirates’ and who then went on to become the King of Algiers) Ali Pasha’s fleet was the cream of the Mediterranean. His crews were all well experienced and he had 25,000 soldiers of whom 2,500 were the crack Janissaries.

A Janissary was a European boy (usually Greek or Albanian) taken captive by the Ottoman Turks and then raised, trained and indoctrinated in special schools to be crack Muslim troops.

The Christian Holy League were a sort of sixteenth century 'Coalition of the Willing' formed with the express intention of breaking the Ottoman Turks stranglehold on the Mediterranean Sea. Commanded by an Austrian called Don Juan who was the illegitimate son of the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V and thus the half brother to King Philip II of Spain, the Holy League fleet had 212 galleys (of which 6 were the superb, heavy galleasses) from Venice, Portugal, Spain, all the coastal Italian city states and the Knights of Holy Order of the Hospitallers.

The Christian fleet was manned by 12,920 sailors, 43,000 rowers and some 28,000 fighting troops, of which some 13,000 were German and Italian mercenaries. An interesting detail is that the Spanish Royal Marines are the only surviving unit to have taken part in the battle of Lepanto. Another such detail is that the author Miguel de Cervantes (who wrote ‘Don Quixote’) also fought and was wounded at Lepanto.

A galleass was the ‘super carrier’ of the sixteenth century Mediterranean world. Originally they were converted merchant ships made obsolete by the introduction of Round ships but they soon developed into the largest class of galley, often mounting upwards of fifty guns and having a full sailing rig. Unlike a galley, a galleass was able to deliver a full broadside and that made them extremely valuable at Lepanto.

I should explain that at this point in history, a 'galley' was a warship whose primary weapon was not the ram as was the case in the ancient world, but rather the cannon. Sixteenth century galleys had a forward battery of guns, which, usually, pointed forwards, or were splayed out to cover a full 180 degree's from the bow of the ship. The secondary weapon of the galley in this period was the marine soldier and blasting, then boarding an enemy was how the sixteenth century galley operated.

The two fleets drew up in the bay and deployed their forces. Don Juan had his galleasses towed to the fore where they turned sideways to the enemy so their heavy guns could be brought to bear. The Galleasses had to be towed because they were slow and unlike galleys mostly relied on the wind. Once they were in position though they were lethal and soon started making splinters of the Turkish ships.

Don Juan himself, aboard his flag ship the Real, remained at the centre of the line of ships that spread out behind the galleasses in four divisions. It should be noted that a line of galleys faces the enemy head on, where as galleasses, like ‘ships of the line’ face them broadside on. Don Juan, nobody’s fool, also left some 38 galleys to the rear as a reserve.

Ali Pasha, aboard his flag ship, the Sultana, split his force into three groups with Chulouk Bey to the North with 56 ships and Uluj Ali to the south with 93 ships. He left a mere 8 galleys and 22 galliots in reserve.

The battle began with the Turks advancing to meet the Christians. In order to do this they had to pass the six galleasses which naturally broke up the Turkish formations as the heavier ships pelted them with gunfire. Once this obstacle had been passed by however the two sides fell into combat.

To the south Uluj Ali managed to out fox the Genoese commander, Doria. Feinting southward he managed to create a gap between Doria’s galleys and the main Christian fleet when Doria tried to counter Uluj Ali’s flanking move. Doria’s over reach left a great hole in the Christian line which Uluj Ali immediately took advantage of by attacking the Christian centre where he took the flagship of the Maltese Hospitallers, the Capitana, killing every one aboard, including the Hospitallers commander Giustiniani, who was cut down, 'Kurasawa style', by no less than five arrows. Don Juan brought up his reserve of 38 galleys to counter Uluj Ali’s attack and the Italian Muslim was forced to flee.

In the north, Chulouk Bey had managed to out manoeuvre the Christians, getting 6 galleys onto the Christian flank and killing the Venetian commander Agustino Barbarigo. The Europeans turned to face this threat but it was only the arrival of one of the galleasses with its heavier guns that saved the northern division.

In the centre, both fleets were going hard at it with great losses on either side. Don Juan had already called up his reserves to deal with Uluj Ali’s attack and now the battle reached its climax with the Christians engaging the Turkish flagship. The Europeans sent in their heaviest troops, the Spanish tercios, who were heavily armoured pike men, and the Turks responded with their Janissaries.

Twice the Janissaries pushed the Spanish back, but on the third attack the Turks caved and the Sultana was taken.

Despite standing orders to take Ali Pasha alive, the Spaniards cut off his head and raised it on a pike. This was the last straw for the Turks. Once they saw their commanders head raised high on the Spanish flagship they lost heart and soon disengaged. The battle was over and the Christians were victorious.

Naturally they gave the credit to the Virgin Mary who they argued had intervened on their behalf.

The aftermath of the battle was long lasting. The Ottoman Turks had lost 30,000 men and the bulk of their fleet and though they set about replacing their lost ships, they never managed to regain their martial superiority in the Mediterranean. The Ottoman Empire continued to attack Europe by land until eventually its vigour was exhausted. The empire finally fell in 1923 and was eventually replaced by the modern state of Turkey.

For the victors, Lepanto was also a dead end. Instead of taking advantage of their success the Europeans fell to bickering amongst themselves and no further attempt was made to capitalise on Don Juan’s victory.

Don Juan himself was appointed governor of the Spanish Nederland’s by his half brother, the Spanish King, in a vain attempt to curb his ambitions. Don Juan agreed to the position only if he were allowed to marry Mary I of Scotland though. Since Mary was then a prisoner in England, this plan called for an invasion of England and hey presto, Don Juan went and died two years later in Bouges before his ambitious plans could be executed.

For the Galley, Lepanto is the grande finale. The galley as a ship type would cotinue to play a role for several centuries but after the battle of Lepanto there would never be another pure galley fleet against galley fleet engagement.

4 comments:

Excellent account - but I've a few comments.

Due to lack of time and (for some reason) a pitifully slow connection today, I'm not putting in sources. Anybody reading this should take it with a whole heap of salt. Nevertheless:

Christian galleys carried more guns than Turkish ones; about 5 : 3. I'm not sure about weight / quality / rate of fire / accuracy.

Galleass had their heaviest guns facing forward. Positioning them broadside suggests that lots smaller guns were expected to be more useful than a few large ones, which sounds reasonable.

Galleass incorporated thicker timbers than galleys, possibly enough to resist hostile fire (guns might well have been far inferior to later ones that could penetrate ships' hulls).

And the questions:

I seem to remember reading about why the galleass were towed (as they *had* oars, even if they favoured sail). Does anyone remember this?

Turks used (relatively) numerous archers. These could engage at a great distance, but I suspect that archers were not overwhelmingly effective against whatever light protection a galley crew could use. Christians could have engaged at closer range (as, all things being equal, they had larger / heavier boarding crews), or possibly used firearms that could penetrate galley superstructures (but this could be a bit early).

Oleg

Comments are always welcome!

With regards to the questions. My understanding of the galleasses is that they had oars but not nearly enough to make them as fast as standard galleys. When these ships were merchant vessels this was not a factor, but once they were converted to warships, they had to be towed if there was not enough wind or else they couldn't keep up with the fleet.

The galleass seems to be one of those class of ships that defies description because there just weren't that many of them made and those that were, were all different. Some are described as having an upper gun deck where as others had guns in between the rowers.

As you say, the biggest guns pointed forwards but that was more often than not true of the later ships of the line.

I haven't much of an idea as to how heavy the broadside from a galleass was. In the initial Turkish advance at Lepanto, the six forward galleasses put down enough fire to sink two Turkish galleys outright but this means nothing without knowing the range. (I need more books)

The Turk archers were one of the factors I missed out. They were indeed effective and in most accounts I've read are considered the next best thing the Turks had (the Jannissaries being the best). By all accounts the Turks almost won the battle by a combination of out flanking feints and superb archery, but were defeated, rather quickly, by superior firepower and the Spanish soldiers ferocity. The battle only lasted five hours.

I'm now looking for accounts of a major battle which featured carracks against galleys... any idea's?

Thats odd, my comment doesn't register on the main page.

Post a Comment